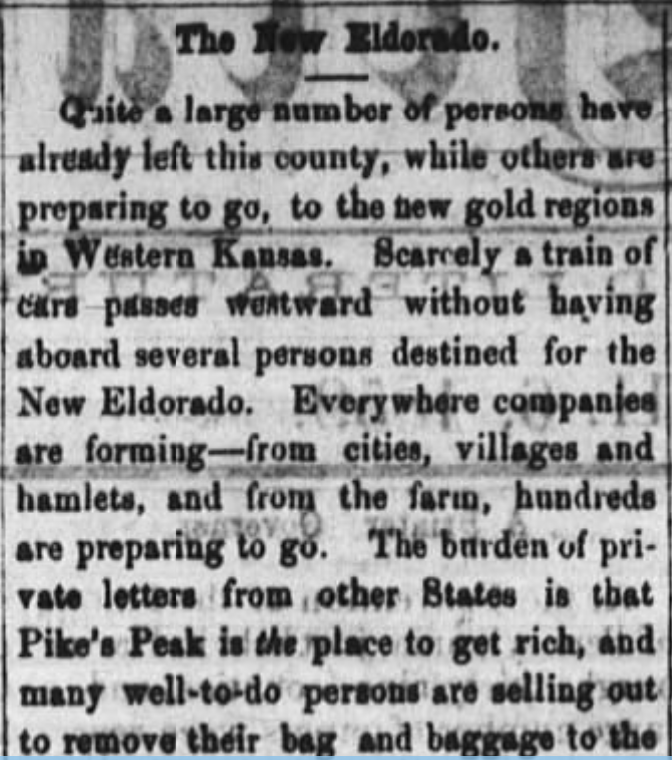

6 Apr 1859, p. 2.

Gold was found in streams in an isolated part of the West. The word spreads and soon thousands of men are pouring into the area to seek their fortune. But this is not California in 1849. This is Colorado and the year was 1858.

For years prospectors had suspected there was gold in the Rocky Mountains, but no significant find developed. Then in 1858, ten years after the California Gold Rush, gold was discovered near present day Denver and newspapers announced it to the world.

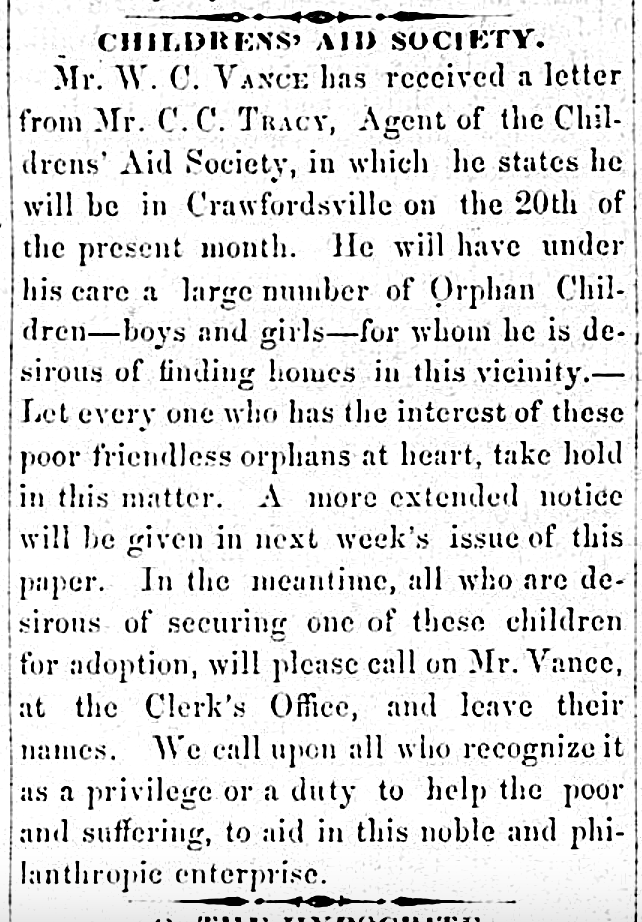

‘Pike’s Peak or Bust’ was the cry of people who rushed to that area. They were people looking for a bonanza. The Panic of 1857 had been hard on the Midwest. Railroads and banks failed, grain prices had fallen over 60%, and farmers defaulted on their mortgages. For many there was little reason to stay on a bankrupt farm while the newspapers reported that miners were finding gold nuggets in Colorado.

William J Holman of Hamilton County, Indiana, had recently lost his job promoting and managing railroads. The gold fields of Colorado were probably attractive to a man facing financial problems and social rejection. So in 1859 he packed up his wife and three children and headed to Pike’s Peak.

Holman and several others were prospecting for likely mining claims when some of their party became discouraged and began talking of turning back. Soon, though, ‘color’ or flecks of gold began to show up in their pans. It was agreed to stay and investigate this creek. Holman was said to respond “Yes, let us tarry, all,” thus, giving the name for the new town that grew up on their mining claim – Tarryall,

The site did ‘pan’ out and a significant amount of gold was mined. When new prospectors came, though, they said the original group’s claims were greedily large. Custom dictated that a miner only claimed the amount that one person could work. They nicknamed the site ‘Grab-all’ and went down the creek and named their town ‘Fairplay.’

Joseph Talbert moved his family to Tarryall, but he died of pneumonia within a month. Gold boom towns were not healthy places to be. Poor sanitation and poor housing meant that disease and exposure led to fatalities. William Holman lost his wife and two of his children to disease. In 1861 he married Kate White.

Another Hamilton County group that caught the gold fever were the Talbert, White, and Stubbs families. All related through marriage or blood, eighteen family members made the trek across the plains over two years. Four siblings, Enoch, Asa, Elizabeth and Joseph Talbert, along with spouses and children came in 1859. Another sibling, Alvin, saw his sister-in-law, Kate White and two brothers-in-law, Isaac and Mordecai White, leave Indiana for Colorado in 1860. Their uncle, Robert Harvey Stubbs, and his family set out the same year.

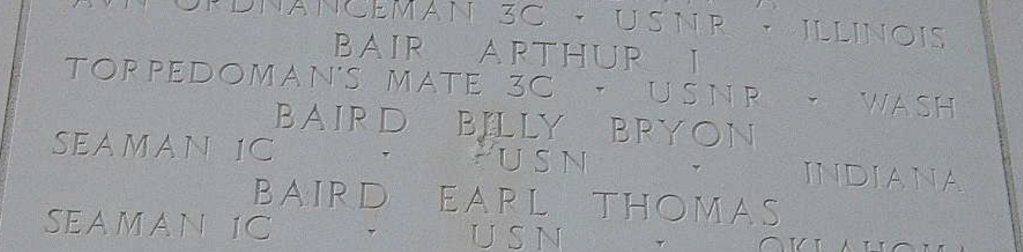

So how did these displaced Hoosiers fare? William and Kate Holman evidently made enough to get back to Indiana and set up in another railroad venture, but not enough to want to stay in Colorado. Isaac and Mordecai White returned to Indiana with empty pockets within a year. Robert Harvey Stubbs opened a hotel in a neighboring town. Joseph Talbert’s widow, Johanna, and their children went back east, but in 1868 when the boys were older and wanted to try their hands at mining, they returned to the gold fields. Her son Job was killed by Indians in 1870. Her daughter, Amanda, married a saw-mill owner and businessman. Asa Talbert joined the Army. Enoch Talbert stayed in Colorado and became a carpenter. Seth and Elizabeth Talbert Beeson stayed and he worked as a cooper. For most, Colorado became their home not because of the Gold Rush, but because of the opportunities offered in the new territory.

Connection: John B. Page was my 1st cousin 5x removed. He married a sister of Joseph Talbert so all these Talberts, Whites, and Stubbs are his in-laws.